When a Forest Comes Back to Life

The pickup truck came to a screeching halt when I asked our driver to pull over. I had just seen the starting point of this story: bare ground, fresh-cut trees, scattered logs, and a small herd of cattle staring back at me from a stripped hillside.

We were driving through the Andes in Antioquia, Colombia — about two hours west of Medellín — on our way to film Terraformation’s Sembrando Futuro 2.0 project. Rolling hills stretched in every direction. Many were bare after decades of cattle grazing and deforestation.

I stepped out with my camera and started filming. This was my first time visiting one of our restoration sites in person. And in that moment, I realized how much of the story you miss from behind a screen.

I spent three days in Colombia in November 2025 with a small film crew documenting the project’s progress since planting began in 2023. As a product marketer, I spend most of my time looking at dashboards, satellite data, and reports. This trip was about seeing the work on the ground.

Being in Colombia reconnected me with the mission we at Terraformation are working toward every day: large-scale forest ecosystem restoration to slow the climate crisis and help provide a healthy, thriving Earth for future generations.

And it reminded me of something simple: even when the challenge is planetary, climate work always starts locally.

A landscape shaped by cattle

Driving through the region throughout the trip, the pattern was obvious. For decades, a cow has been worth more than a forest. Cattle means food, hides, income, and therefore, security.

The result is a landscape marked by bare ground, scattered trees, and limited canopy. In some places, cattle roam freely. In others, there are no animals at all. And yet, the cattle don't seem to need this much land. Again and again, we saw them congregating under the few remaining shade trees, seeking relief from the heat and humidity.

Alongside pastureland, you’ll find banana plantations, eucalyptus plantations, and coffee farms. Eucalyptus, native to Australia, grows easily here and supports furniture and construction industries, but its plantations often limit native plant growth by altering soil conditions, water availability, and understory dynamics.

By replacing forests with cattle and monoculture crops, communities lose more than trees. They lose natural systems that regulate water, buffer against floods and landslides, and moderate local climate. They lose biodiversity in one of the most biologically rich regions on Earth. They also lose access to medicinal plants used for generations, along with food sources like fish, game, mushrooms, and wild plants that depend on intact forest systems.

This is where Terraformation and Fundación Grupo Argos come in.

Reforestation, Behind The Scenes

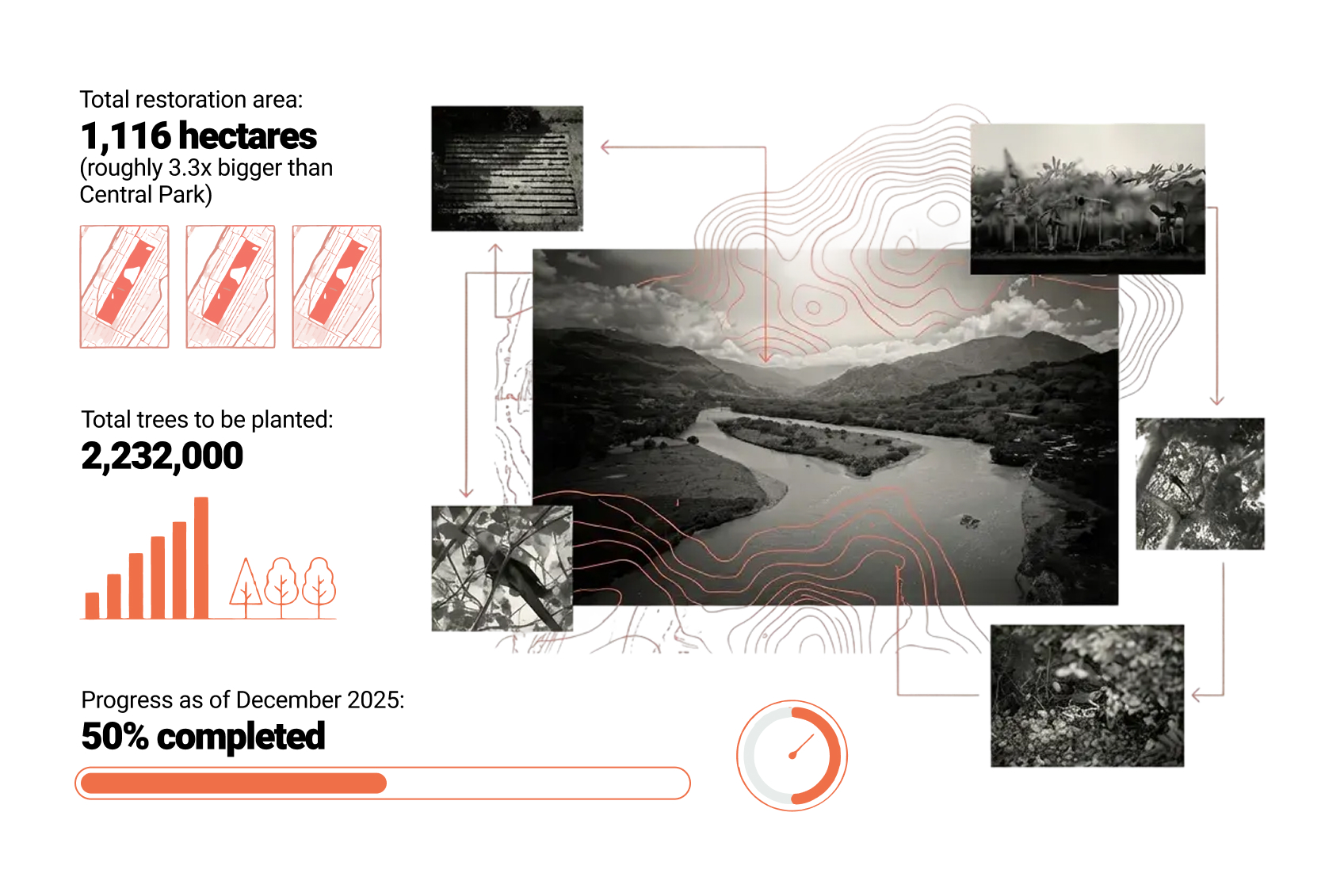

CIRCA, the first research and conservation center for tropical forests in Antioquia, is part of a broader alliance Terraformation entered into with Fundación Grupo Argos in 2022–2023 under the Sembrando Futuro 2.0 project. Our partnership now spans more than 1,160 hectares across 19 landowners, from private or family lands, to private organizations, NGO’s, and public territories. Conservation here is designed to be inclusive and replicable.

At CIRCA, we conducted three interviews that anchored the story.

- Maria Camila, Director at Fundación Grupo Argos, shared how the project brings together a complex network of actors: from landowners to technical experts and schools. Her role sits at the intersection of these relationships, ensuring alignment.

- Andrés Contreras coordinates environmental education programs for Fundación Grupo Argos. His work takes him directly into schools across the region, working with students and teachers to explain what climate change means locally, why conservation matters, and how restoration connects to water, food, and livelihoods. Today, these programs reach 26 schools, more than 3,800 students, and 168 teachers. In many cases, schools also host small nurseries or seed banks, giving children hands-on experience with restoration in their own communities.

- Elber Ledesma represents landowners across the territory and leads processes tied to protected areas and conservation agreements. In a country shaped by decades of conflict, clear land tenure is critical to protecting the credibility and long-term success of any restoration project. Elber works closely with private landowners across the region who see this work as a legacy project, something they want their children to understand, protect, and carry forward.

The facility at CIRCA produces 500,000 plants per year with a lean staff of seven. Across a broader network of seven regional nurseries, these plant-powerhouses can produce roughly one million trees per year.

The birds seem to love it here too. While filming these interviews, we spotted wild macaws eating the seeds on a tree a few feet from our camera set up.

Education, investment, and impact

Shifting land-use practices requires shifting mindsets, especially after decades of ranching traditions. Children are often the bridge. By involving students in managing seed banks and connecting them with nature through field trips to forests and monitoring birds and mammals with camera traps, the project builds long-term stewardship into the next generation.

Land ownership is equally critical. Some of the earliest conservation agreements were signed by women, sisters who wanted their children to understand why this land matters.

Our carbon credit buyers, including Climeworks, hold us to some of the highest standards in the carbon market. Before investing, Climeworks reviewed dozens of projects and selected just four. What differentiated this project was rigor in science, data, and execution.

Dynamic Baselining: In line with the latest Verra VM0047 methodology, we track control plots with similar baselines near our project sites and compare them to our restored areas using satellite imagery. The difference over time represents how many credits are issued, proving planting interventions results in more carbon sequestration than what would happen naturally.

From nurseries to the field

After CIRCA, we went through the logistical motions of what it’s like moving the seedlings to the planting sites. We arrived at Biosuroeste, where active planting was underway with Tekia on site. Tekia serves as the technical arm of the restoration effort, bringing decades of planting experience to our project sites. We also saw how they use our forest tracking software, Terraware, to precisely record what trees are planted and where for monitoring, reporting, and carbon credit verification purposes.

Biosuroeste sits within a larger park landscape of roughly 600 hectares. Its history is complex, shaped by conflict and later transferred to public ownership for social and ecological restoration. Today, Biosuroeste is designed to integrate people with nature and prove that restoration can coexist with other productive activities. Our work happens alongside cattle systems, agroforestry, ecotourism, recreation, and conservation areas.

We are planting 19 native tree species, two of which produce fruits used by local communities to make biodegradable soaps and natural dyes, providing an additional source of income.

Planting sites

During the other two planting site visits, I learned details that don’t always make it into reports. Certain grasses can protect seedlings early on. Dense ferns give way once pioneer species establish but need to be cut back periodically. Planting only happens during the rainy season, so no watering is required.

One planting site required a 45-minute walk through a dense forest. At La Capota, the landowner is the Tarso Municipality, which is partnering with us to protect the water stream that feeds the municipal aqueduct. For the government, providing clean water for the municipality is the primary motivation for this restoration project.

Another site – called El Morro – sat at the top of a mountain, above the clouds on steep terrain. These are challenging, diverse landscapes, spanning low to high montane ecosystems.

Closing reflections

Carbon credits can feel abstract. We’re measuring carbon dioxide sequestered by trees over decades and issuing Verified Carbon Units in return. That’s not the easiest story to tell.

But here in Colombia, everything feels tangible. You see trees taller than you after one year. You meet nursery workers earning a living. You see insects, birds, and endangered animals returning. You drink water from the faucet without concern, knowing the forest helped purify it.

Colombia is often called la tierra de la eterna primavera, the Land of Eternal Spring. Sun, water, humidity, and warmth create ideal conditions for growth. The trees grow fast. These ecosystems can recover, even after severe deforestation, but recovery still requires patience, monitoring, scientific rigor, and landowners who believe the land is worth restoring.

The project is named Sembrando Futuro 2.0: sowing the seeds of the future.

After seeing it firsthand, that future feels present.